Materials Logistics Strategy Excerpt

The following excerpt is from Chapter 4 of the Nevada State Rail Plan, pages 4-8.

C. Supply-Chain Infrastructure Planning

Transportation Infrastructure Can Be Conceived to Support Whole Supply Chains

The United States enjoys abundant natural resources and robust private-sector commerce, along with ongoing increases in truck activity. Consequently, transportation departments in every state are struggling to fund road construction and maintenance to keep up with growing road wear and congestion. Meanwhile, the country benefits from a freight rail system almost entirely funded and maintained by the private sector. Given the critical role of transportation infrastructure in our nation’s most important supply chains, states must lead the transition to a balanced use of roads and rail. Nevada’s current surge of industrial development and its adjacency to California and West Coast ports present a rich opportunity to plan infrastructure for supply chain optimization that minimizes the public costs and community impacts of this growth.

What is commonly called “supply chain optimization” has been narrowly focused on individual companies’ material sourcing and product distribution. Consequently, in 21st-century North America, neither the marketplace nor the public sector has been able to comprehensively plan infrastructure for efficient supply chain systems.[1] For example, in 2008, at the height of America’s ethanol-production boom, hundreds of billions in investment capital poured into the ethanol industry to fund individual “competing” infrastructure projects. Ethanol production skyrocketed while the ad hoc transportation and distribution system remained inadequate for meeting the nation’s essential energy needs.

Nevada’s long-standing mining industry presents a compelling opportunity to apply “whole systems” supply chain infrastructure planning. Section C.2 describes the NVSRP’s Mining Materials Supply Chain Logistics Strategy. Nevada’s mines in the 21st century have become a global provider of silver, gold, copper, and “strategic minerals” critically needed for electronics and alternative energy systems. Supply chain infrastructure planning will improve transportation efficiency and enhance market access for Nevada’s mining industry. This opportunity has been well received across the industry. During a recent Connect Rail Nevada Regional Meeting, the North American head of logistics for a Nevada gold mining company expressed their company’s “interest in connecting with their South American operations” via rail through West Coast ports. Nevada has a timely opportunity to expand and diversify its commercial base by empowering its mining industry with a rail-enabled logistics system that connects producers, suppliers, and customers across the state and the world. The logistics system outlined in the Mining Materials Supply Chain Logistics Strategy would enable Nevada to retain more value in the supply chain as it expands in-state “Beneficiation.” Beneficiation refers to the economic and environmental improvements experienced by natural resource-producing regions as they move up the mining value chain. Section C.2 provides a global perspective on Nevada’s Beneficiation opportunity. First is an overview of the state’s mining activity.

C-1. Nevada’s Mining Industry – Overview & Trends

Mining remains a significant industry in the Nevada economy, with a gross value of $8 billion in minerals produced in 2018.[2] Nevada Mining has consistently ranked in the top 10 in global investment attractiveness for the past five years, including a third-place ranking in 2019.[3] The mining industry provides a fairly small share of overall Nevada employment (1.2% in 2016, predominantly in rural communities). However, the two major mining companies, Barrick Mining and Newmont Mining, consistently rank in the state's top ten highest assessed taxpayers. This speaks to the fact that the mining industry is a powerful economic contributor to Nevada.

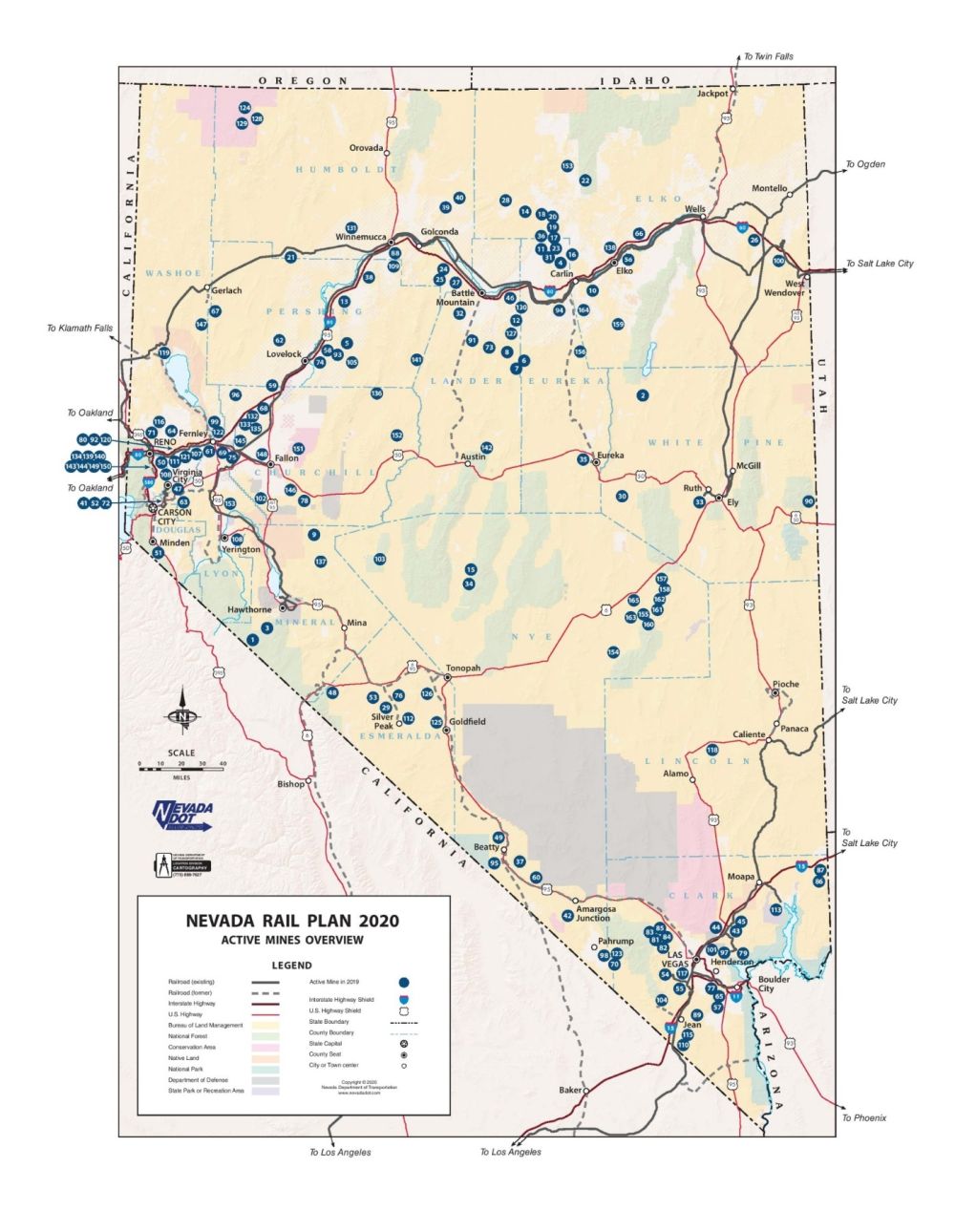

As shown in the map below, 20 major minerals are mined in Nevada, with 103 active mining sites as of 2018.[4]

Gold, silver, copper, barite, magnesium, and, increasingly, lithium are among the more essential minerals mined based on revenue and production. Nevada is the fifth largest gold producer in the world and is responsible for 83% of U.S. gold production.[5] Nevada ranks second in geothermal energy mined in the U.S. (California is the top producer).

Due to stable prices, a conducive regulatory environment, and continued population growth, the Nevada mining industry in gold, silver, etc., is projected to continue strong for many years. The projected exponential demand for electric vehicles and batteries will require significant increases in lithium and copper production.[6] In 20 years, 56% of all light-duty commercial vehicles and 31% of all medium-duty commercial vehicles are projected to be electric. [7] Demand for copper in vehicles is expected to increase by 1,700 kilotons by 2027. Tesla operates their “Gigafactory,” a lithium-ion battery and electric vehicle subassembly factory in Sparks. Nevada has the only mine producing lithium in the U.S., called the “Lithium Hub,” located near the Tesla Gigafactory facility.

The Nevada Department of Employment, Training, and Rehabilitation projects that in 2026, employment in the Natural Resources and Mining sector will remain stable at a 1.1% share of the overall state workforce, compared to a 1.2% share in 2016.[8]

Table 4-1: Nevada Long-Term Industrial Employment Projection from 2016-2026

| Industry Title | 2016 Employment | 2016 Employment Share (to all NV Industries) | 2026 Employment | 2026 Employment Share (to all NV Industries) | 2016-2026 Total Change |

| Natural Resources & Mining | 16,671 | 1.2% | 18,345 | 1.1% | +1,674 |

C-2. Mining Materials Supply Chain Logistics Strategy

Elevating the planning focus from individual projects to encompass the whole network of mining industry supply chains will deliver measurable financial, economic, environmental, and social benefits to Nevada’s businesses and communities. The foundation for this supply chain strategy exists as Nevada already engages in vigorous cross-sector collaboration among its mining industry, government, and academia. The Nevada Mining Association, the Nevada Division of Minerals, the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, and the Mackay School of Geology and Earth Sciences collaborate with each other and with the many mining and mining supply companies in the state. Each organization has provided input into the Mining Materials Supply Chain Logistics Strategy.

Following is an inquiry-based outline of the analytical process for “mapping” the Nevada mining industry and improving its supply chain efficiencies and opportunities. This supply chain mapping will guide Nevada to a system for transporting and distributing mining materials before and after extraction and will inform the smartest siting of new processing and manufacturing facilities.

Mapping the current mining materials and supply chain

- Where is each mine located in the state?

- What company owns each mine?

- What company operates each mine?

- What activity is going on at each mine? What materials are mined?

- What supplies in what quantities are brought into each mine?

- Where do those supplies originate?

- What transportation mode(s) and facilities are used for each supply item?

- What ore elements and volumes are produced at each mine?

- At which mines are the ores currently refined onsite?

- If refined onsite, where and how are the refined minerals shipped?

- Where are the in-state and out-of-state processing, refining, and smelting facilities?

- Where and how is each ore element transported to offsite refining or smelting?

- What quantity and type of byproducts are generated at each mine, and where and how are they shipped?

- What quantity and type of waste products are generated at each mine, and how and where are they disposed of?

Mapping the materials and supply chain for mines in development

- Apply the same questions above to mining projects, proposed or in development

Mapping current transportation, storage, and distribution facilities

- Where are the in-state rail- and truck-served mining supply warehouse and unloading facilities?

- Where are the in-state rail- and truck-served mining materials distribution and storage facilities?

Discerning the optimal mining materials and supply chain logistics system

- What are the requirements and metrics for mining supply provision?

- What are the requirements and metrics for mining materials transportation?

- What are the requirements and metrics for mining materials storage?

- What are the requirements and metrics for mining materials distribution?

- What is the competitive landscape of mines in the state?

- What new supply chain developments would enhance mining operations?

- Where can new rail line construction enhance mining operations and minimize transportation costs and impacts?

- Where can new rail loading facilities enhance mining operations and minimize transportation costs and impacts?

- Which communities and residents should be included in the evaluation of siting new facilities and infrastructure?

Diversification and Beneficiation—logistics for new processing and associated product manufacturing

- Where can new smelting, processing, or refining facilities be optimally located in relation to the needs, benefits, and impacts of transporting mining products, by-products, and waste streams?

- What new associated product manufacturing facilities are made viable by Nevada’s mining activity and location in the market?

- Where can new associated product manufacturing facilities be optimally located in relation to the rest of the supply chain?

The Mining Materials and Supply Chain Logistics Strategy outlined above can be stewarded by OnTrackNorthAmerica as a collaborative effort among the University of Nevada-Reno, the Nevada Mining Association, and the Nevada Bureau of Mines. The Nevada Mining Association’s co-sponsorship of the project will go a long way toward fast-tracking the effort and minimizing the staff time required to map out the entire mining supply chain system. Conversations in the state during the development of the NVSRP have provided early indications that the project is well-received by the association and its members. An efficient budget could be funded by a combination of potential sponsors such as the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, the Nevada Mining Association, individual mining company sponsors, and Nevada charitable foundations. Several federal agencies that offer planning grants, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, particularly for rural areas, may be motivated to co-fund this innovative effort as well.

Rail lines and rail-served transload, storage, and distribution facilities conceived to improve efficiencies and expand opportunities for Nevada’s entire mining industry will provide the infrastructure backbone for beneficiation, a transformational enhancement of the state’s economic well-being.

C-3. Beneficiation of Nevada’s Natural Resource Economy

The western states of the U.S. are rich in primary mineral resources, contributing significantly to the nation's wealth and economic security. These extractive resources are abundant and varied, ranging from volume aggregates to high-value precious metals. Whereas the agricultural Mid-West and Great Plains are America’s breadbasket providing food security, the western states provide similarly important resource security. Thanks to this natural endowment, the U.S. does not suffer the same vulnerability as other global economic powerhouses such as China, Japan, and India, which are far more dependent on importing primary resources.

The value of extractive goods, especially the non-oil resources found in Nevada and other western states, goes beyond economic security and resource self-sufficiency. Materials from aggregates to copper, lithium, and silver are crucial feedstocks for U.S. manufacturing, technology, and construction industries and are major revenue-earning exports.

Despite this disproportionate economic importance and value contributed by Nevada mining, the state is one of the lowest contributors to the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).[9] This dichotomy is partly explained by the methodology employed in GDP calculations, but it also reflects how the state is not taking full advantage of its significant natural resource endowment. The state has a strong mining focus on the initial stage of a four-phase value chain, which starts with extraction and moves through processing to manufacturing and distribution. There are historical reasons why the development of Nevada focused on extraction, but looking ahead, there is a clear opportunity to change the dynamics of the resources supply chain, bringing more of the higher value activities into the state.

There are economic and environmental benefits to Nevada’s embrace of higher-value activities. This is referred to as “Beneficiation,” an economic development term for a strategy that leverages an existing sector to create additional jobs and economic activity in subsequent value chain stages. In the resources sector, this often means creating new industries that process a region’s resources locally rather than simply exporting raw materials. In the case of gems, this could involve cutting and polishing the stones. It could be building capacity in the refining and manufacturing processes for metals. As the Nevada Bureau of Mines 2018 report highlights, “Opportunities for Precious Metals Toll Processing and Copper Concentrate Processing in Nevada”[10]…

“…a case could be made for establishing a concentrate processing facility in Nevada if production from other western states that are now exported and the potential output from undeveloped resources in Nevada and other states are considered along with the current Nevada production.

“Developing a concentrate processing facility may attract downstream copper facilities such as rod plants, wire manufacturers, brass mills, and copper-alloy manufacturers.”

“Transportation of concentrate to a new processing facility requires accessibility to highway and rail systems.”

“Tentatively, a swath of potential locations along the I-80 corridor west from Wells to about Fernley, then south between highways US-95 and US-95A toward Yerington is initially proposed. At first look, this swath of land appears to provide access to transport and utilities required to support a processing facility. Potential areas for siting a concentrate processing facility are highlighted on the map in Figure 1. These areas have access to highway and rail systems, the electrical grid, and natural gas pipelines as well as having no current sources of air emissions within the boundaries of the basin.”

Although local beneficiation is often recommended in development strategies for resource-rich but economically poor countries in Africa, Asia, and South America, it applies equally to major economies such as Canada or Australia and is highly applicable to Nevada.

The state’s rail strategy is key to realizing the economic development advantages of beneficiation. Advancing higher-value industries requires an effective and reliable freight transportation network with sufficient capacity and scalability to support growth. This growth can only be served when Nevada’s rail network is augmented to accommodate rail movement between in-state businesses. As pointed out in the freight data analysis reported in Chapter 2, the share of intra-state freight rail activity (originating and terminating the same railcar load of freight within the state) is about .25% of overall rail traffic in Nevada.

Fortunately, as described in Chapter 2, Nevada enjoys an existing core of rail infrastructure, including operational and dormant freight lines and sidings, and relatively attractive topography for building new rail connections. Therefore, rail can be a powerful catalyst for a successful beneficiation program in Nevada, providing the robust freight infrastructure necessary to support inbound, outbound, and intra-state supply chain movements. Without rail, beneficiation will be limited by the constraints of road-based transport and its consequent environmental and congestion impacts.

The economic benefits are significant for the state. By expanding up the mining value chain, Nevada will realize increased employment, a greater diversity of jobs, higher salaries, and increased state tax revenues from a growing business sector and expanding population. These benefits create a virtuous circle whereby greater state revenues fund infrastructure improvements, attracting even more businesses and residents.

The relative impacts of beneficiation differ by commodity but can bring substantial economic growth to all primary extractive resource sectors. Case studies, research, and analysis around the world demonstrate that any movement up the value chain generates economic benefits. The greatest economic benefits derive from the increased value of added-value processing and manufacturing. One example is when the Indonesian government restricted the export of raw nickel ore, bauxite, and tin in 2014 to encourage the development of local processing capacity. This resulted in exports of refined metals growing at an annual average rate of 9.2% over five years (to 2019), from $9.3 billion to $13.4 billion.[11] In 2019, China implemented policies to reduce exports of raw rare earth elements, triggering new economic development from the downstream processing of products such as magnets, catalysts, alloys, and glass. South Africa has also attempted to develop a diamond-cutting and polishing sector by restricting licenses for the sale of mined diamonds.

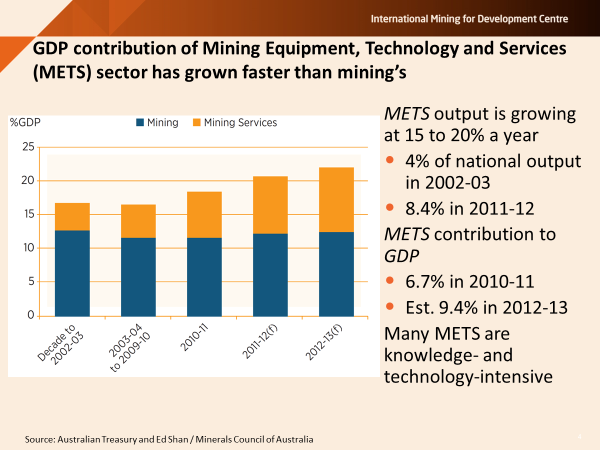

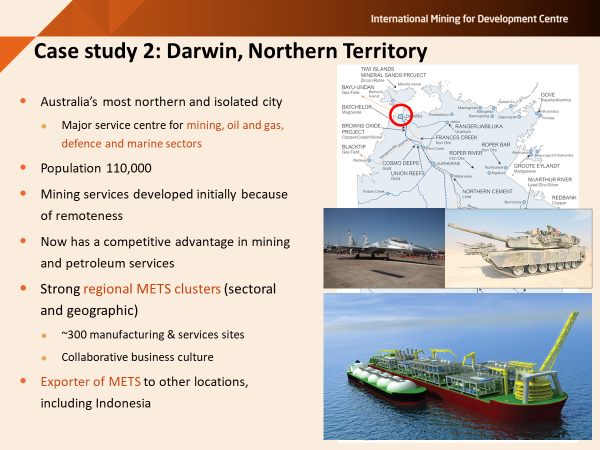

Examples of beneficiation are not limited to the developing world. In 2003, the Australian government sought to move up the extractive industry value chain to reduce commodity price volatility and over-dependence on exporting raw materials to China. The country took creative steps to bring diversity and high-value production into its mining states. One successful approach took advantage of mining industry clusters to create a Mining Equipment, Technology, and Services (METS) sector. The METS sector has grown into a major economic contributor to Australia, growing at double the rate of the mining sector and contributing an equal share of GDP by 2012.[12] See the tables below from the International Mining Development Centre/World Bank.

This Australian example shows that the opportunities for economic benefits from beneficiation expand to new and aligned industries in addition to direct downstream manufacturing. A further benefit is that diversifying economic activity up the mining value chain reduces the impact of fluctuating commodity prices on the state’s economy. Having downstream industries in-state provides diversity, reducing the proportion of output affected by often volatile commodity prices in a global market.

Nevada is positioned to benefit substantially from beneficiation simply because its location in the continental United States gives it direct access to North America, the world’s largest economic zone. Having such a large market means Nevada depends far less on international exports than other developed, resource-rich countries such as Australia and Norway. A dependency on exports gives leverage to the importing nations, who will seek to keep a greater share of economic value by importing raw materials rather than processed or manufactured products. For Nevada, a huge and free internal North American market connected by transcontinental transportation corridors removes this constraint and clears a path for developing an economy that moves up the vertical value chain.

In addition to the economic factors, there are also clear environmental benefits. Nevada’s roads are increasingly congested, and air quality is suffering. High-volume road movements of extracted materials trucked to out-of-state facilities, primarily in California, are a prime cause of these impacts. In coordination with a robust expansion of the intra-state rail network, these truck movements would be redirected to far shorter, less environmentally damaging local road and rail hauls to in-state facilities. Moreover, the additional revenues from beneficiation would fund investments that improve the road and highway network and its integration with rail.

References

- ↑ Vimmerstedt, Laura J.; Bush, Brian & Peterson, Steve, “Ethanol Distribution, Dispensing, and Use: Analysis of a Portion of the Biomass-to-Biofuels Supply Chain Using System Dynamics”, PLoS One Journal, source link, published May 2014.

- ↑ Nevada Commission on Mineral Resources – Division of Minerals, Report “Major Mines of 2018”, source link, page 26.

- ↑ Fraser Institute Survey of Mining Companies, 2019 Annual Survey of Mining Companies, source link.

- ↑ Nevada Mining Association website, source link, website accessed July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Nevada Commission on Mineral Resources – Division of Minerals, Report “Major Mines of 2018”, source link, page 23.

- ↑ Nevada Commission on Mineral Resources – Division of Minerals, Report “Major Mines of 2018”, source link, page 26.

- ↑ Nevada Mining Association, Presentation “Mining Through Uncertainty,” source link, page 98.

- ↑ Nevada Department of Employment, Training, and Rehabilitation, 2016-2026 Long-Term Employment Projections, source link.

- ↑ Statista website, “Which States are Contributing the Most to U.S. GDP?” article, source link, published June 8, 2020.

- ↑ Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Report 57: “Opportunities for Precious Metals Toll Processing and Copper Concentrate Processing in Nevada”, source link, accessed August 26, 2020.

- ↑ Mining.com website, “Indonesia moving up the mining value chain – report”, source link, published July 28, 2020.

- ↑ International Mining for Development Centre/World Bank, Presentation: “Enabling the development of industrial capacity: Resource corridors, clusters and SEZs”, source link, accessed August 26, 2020.

- ↑ International Mining for Development Centre/World Bank, Presentation: “Enabling the development of industrial capacity: Resource corridors, clusters and SEZs”, slide 4, source link, accessed August 26, 2020.

- ↑ International Mining for Development Centre/World Bank, Presentation: “Enabling the development of industrial capacity: Resource corridors, clusters and SEZs”, slide 8, source link, accessed August 26, 2020.